Africans Maketh the (Wo)Man: Black Materiality & Material Culture in the Creation of the Modern World

Musings on The Met Gala and Black Dandyism

Way back in the earliest days of my doctoral program, my first seminar was on early American history. By that time, I had committed myself to the twentieth century—it was fast, it was exiting, it had technology. And as someone raised in the DC area, I also avoided early American history because I’d had my fill of the “Founding Fathers” and the Civil War. But I found synergy between my museum work and this seminar when I started thinking about the actual material culture of the house museums and plantations and historic sites I was exposed to on school field trips (taking fourth graders to Mount Vernon and not telling us it was a plantation is an experience I still recount many many years later). Namely, that the furniture, the furnishing, the fashion, the food, the houses, the streets—everything—were fashioned by Black people or in the context of slavery.

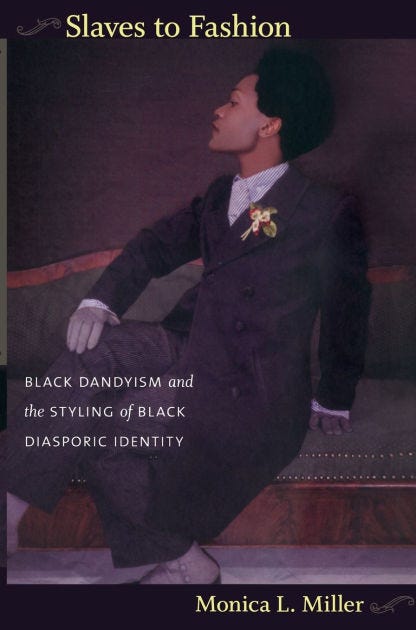

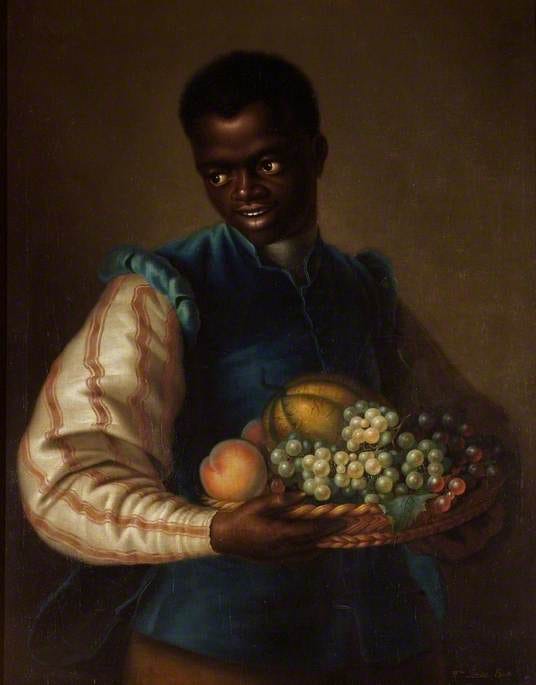

The annual Met Gala for the Costume Institute is tonight, and there has been a lot of excitement about the theme and the accompanying exhibit, inspired by Dr. Monica L. Miller’s 2009 publication, Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity.

In the introduction, Miller argues that the book contends with

“how and why black people became arbiters of style and house they use clothing and dress to define their identity in different and changing political and cultural contexts…the ways in which Africans dispersed across and around the Atlantic in the slave trade—once slaves to fashion—make fashion their slave."

Because of my interest in early twentieth century history, I had blogged about the dandy in that context, where men of the Edwardian and Belle Epoque eras found new ways of expressing masculinity at a time where society was in flux due to colonialism, technologies such as the camera, cinema, and electric light, immigration, the rise of department stores that democratized fashion, and rapidly shifting gender roles. I also blogged about the cakewalk, where African American performers flipped racial stereotypes from minstrel shows on their heads to poke fun at the ways in which the white gaze misinterpreted their behavior and style. My younger mind could not make the connections that I can make today, as a scholar, curator, and published researcher; in light of the The Met Gala’s theme, Miller’s thesis statement about how Black people used fashion to shape a new identity during a long history of denying humanity and equality did not occur outside of how white men in the US and in Europe constantly used fashion to shape their identities (around white supremacy, colonialism, eugenics, etc) to circumvent the increasing access of subjugated peoples to the same material culture they had access to.

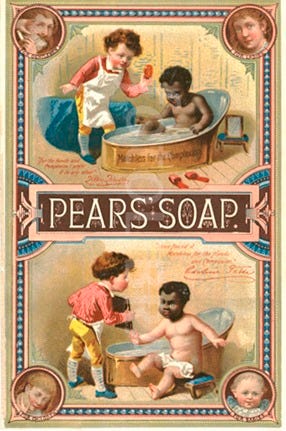

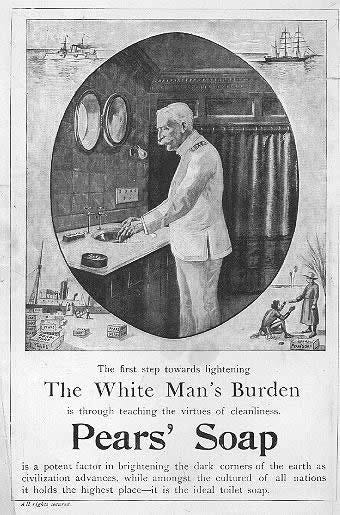

A lengthy sentence to say that the material culture of the Atlantic world was a contested space for legitimacy, humanity, and power. The dandy wasn’t merely an affected figure, it existed throughout the nineteenth and twentieth—and twenty-first—centuries to reveal the tensions around what was masculinity and what was race? It is no coincidence that all of these anxieties around both were visible in the materialities of the growing modernity of Western society. One of my favorite academic texts is Anne McClintock’s Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest where she discusses how the struggle for power in the British Empire can be found in ads for the soap brands advertised to white Britons and British subjects in Africa and Asia.

But to return to my ruminations on material culture and the materiality of Atlantic World, the ideas around representation of Black people, free and unfree, and how that intersected with adornment and self-fashioning are present in the physical objects circulating in abolitionist circles of the late 18th century. I wrote this several years ago when I thought my dissertation topic would be on the material culture of the Black Atlantic; I am returning to it again as I think through the Met Gala’s dandy theme.

Let us consider the Anti-Slavery Medallion manufactured by Josiah Wedgwood in the 1780s. The figure of a partially clothed enslaved man, kneeling, with chained hands raised in supplication, and the sentence “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” curving neatly over his bare head, is rendered in white jasper and black basalt—minerals Wedgwood favored in the late eighteenth century for the casting of the medallions and plaques of famous personages for mass consumption.1

Innocuous though it may seem to modern eyes—a pretty piece of the past at which to cast a passing glance whilst wandering through the European Decorative Arts gallery at the Art Institute of Chicago—; revolutionary its fashioning seemed to late eighteenth and early nineteenth century British abolitionists; a closer reading of the medallion raises questions not only about the commodification of a commodity, but the linkages of taste, civilization, and bondage. One can imagine how smart eighteenth century abolitionists felt as they purchased this fine Wedgwood piece, intending to display both their pleasure in possession of such an object and their personal politics to the public.

Yet, the object of the object, the objection of the object, the object of the objection—the black body—is only visible to satiate the tangible tangle of appetite and enslavement in the early modern world; the very blackness of the basalt molding of the enslaved man, set against the white jasper, reveals the subconscious Othering of blackness in material goods to reveal the whiteness of its consumers. To clarify, without Africans there would be no civilization—either in rendering the black body as legibly uncivilized in contrast to white bodies, or in black bodies existing as, to create, to supply, and to fashion the objects with which white bodies signified their modern, enlightened, civilized identities.

As bell hooks succinctly states in the essay “Eating the Other” in Black Looks: Race and Representation:

When race and ethnicity become commodified as resources for pleasure, the culture of specific groups, as well as the bodies of individuals, can be seen as constituting an alternative playground where members of dominating races, genders, sexual practices affirm their power-over in intimate relations with the Other.

That historians of the early modern Atlantic tend to skate around this linkage of black materiality and the “consumer revolution”—and that meditations on blackness/whiteness, civilization, and consumption are more often found in interdisciplinary fields, such as literature, art history, or anthropology—speaks to the meanings history reads onto material culture. That is, the narratives privilege the stories told by the objects owned and collected by the elites and middle classes (clothing, utensils, jewelry, paintings, etc.), while casting the bodies literally owned by these selfsame subjects outside of the material space. Black bodies are at once stripped of their role in the global and domestic community as simultaneously consumed and consuming, and the Africanness of Atlantic World culture is underestimated.

Histories of the early modern Atlantic world, of slavery, and of consumption, consumerism, capitalism, and material culture rarely converge. When they do, they tend to drift together uneasily, as demands of traditional historiographies weigh on how to tell the story of this complex temporal and geographical area. Through the lens of material culture, I seek to address the linkages of civilization and slavery and consumerism in the eighteenth century, where the concept of modernity—or Enlightenment—and its physical expression via clothing, food, furniture, and other material goods, can only exist through the labor and production of the enslaved.

I argue that the civilization and respectability of the Atlantic World via material culture could only be performed by Europeans because of their consumption of the enslaved and the goods they produced. My thoughts work across the wood grain of the furniture and home goods created by enslaved craftspeople in the Atlantic world and give these craftspeople the starring role in the fashioning—literally—of the age of empire and revolution. When looking at furnishing, fashion, domestic spaces, and design and architecture they are the space where Black people’s labor helped white colonists and Europeans shape their ideas about their modernity and physically built modernity and self-fashioning.

Material Culture

The history of things—or, material culture studies—is a relatively new methodology, though its roots, as Dan Hicks argues, are embedded in the “museum-based studies of 'technology' and 'primitive art' during the late nineteenth century.”2 To recognize its origins is to understand why material culture can often be wedded to the ideas of “civilized” vs “primitive” (or folk) objects, which obscures the production of these objects by “primitive” peoples either residing in or transported to the New World.

Anne Gerritsen and Giorgio Riello push against this obscuring of production, consumption, and trade in The Global Lives of Things: The Material Culture of Connections in the Early Modern World, mapping the history of things in the Atlantic World as spaces created by commodities, which “reconfigured geographies and brought into contact societies living at vast distances from each other.”3 Furthermore, these objects created “‘imagined spaces”—views where they were produced or where they were thought to have come from.” Unfortunately, Gerritsen and Riello’s examples reinforce the emphasis on the things left by elites and place the commodities in the context of the consumers more so than the producers.

Arjan Appaduri argues in The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective for the emphasis to be placed on the traders as “critical agents for the articulation of supply and demand of commodities.”4 To take the middle ground approach, so to speak, positions material culture as a site of negotiation. We see this in Thornton’s text on Africa and the Atlantic, where trade with Europe was influenced by “prestige, fancy, changing taste, and a desire for variety” than a scarcity of industry or commodities. The geographic distance between Europe and Africa, as well as the interiors and the coast, determined the relationship between the explorers and traders of the nations; there was neither wholesale conquer nor naïve commercialism.

When opening up material culture to that perspective, the black body as material via the transatlantic slave trade becomes itself a site of negotiation. As a commodity. As a being. As African. As New World. As consumed. As consumer. The integration of the slave into the European household as thing and as labor blurred the liminal spaces of man and object, or even liberty and bondage.

Sidney Mintz argues in Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History that sugar created “two so-called triangles of trade...the first and most famous triangle linked Britain to Africa and to the New World...the second triangle” ran somewhat in reverse. But both trades involved human cargo—slaves:

Millions of human beings were treated as commodities. To obtain them, products were shipped to Africa; by their labor power, wealth was created in the Americas. The wealth they created mostly returned to Britain; the products they made were consumed in Britain; and the products made by Britons—cloth, tools, torture instruments—were consumed by slaves who were themselves consumed in the creation of wealth.5

In Empire of Cotton: A Global History, Sven Beckert characterizes the role slavery and slaves played in the “re-creation of the world”6 as war capitalism—that is, the violence and subjugation of Africans and Native peoples, coupled with the mechanization of production, built the modern Atlantic economy. Zara Anishanslin probes this a bit in Portrait of a Woman in Silk, but ultimately maintains the British-America relationship; however, she argues that early American history reveals itself to have “cut across regional distinctions”7 through the consumption of luxury goods, such as silk.

The creation of an American identity through material goods was part of the need for gentility, as Richard Bushman argues in The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities. Gentility “bestowed power…it occupied a central position in a far-reaching cultural system…[and] objects or practices”8 bestowed gentility. As such, the ownership of slaves both permitted (funded) the practice of gentility and created the necessary contrast with which (white) gentility was defined and refined.

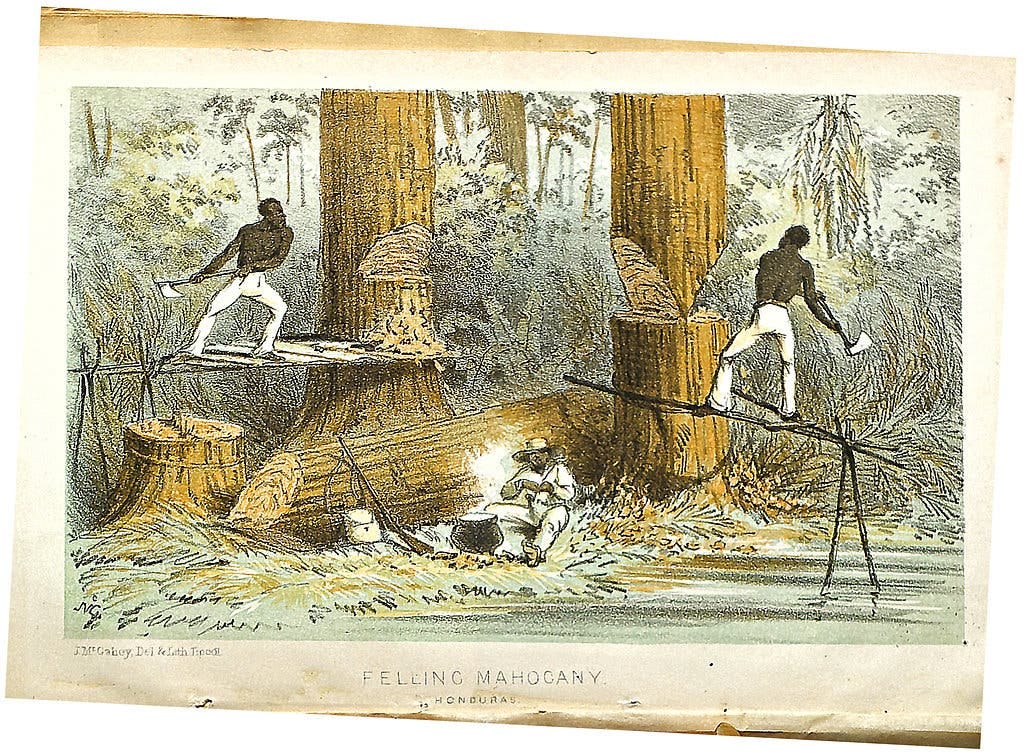

This contrast preoccupies Jennifer L. Anderson’s Mahogany: The Costs of Luxury in Early America. Far more than cash crops and sugar, this dark, supple wood marked a different kind of consumption and gentility. Mahogany, she argues, was “converted into substantial, long- lasting, material artifacts— physical things— that people gradually imbued with a range of cultural connotations that held shared meaning.”9 It is no coincidence perhaps, that abolitionists of the nineteenth century fixated on mahogany—its darkness, its harvesting, its uses, all spoke to the black bodies producing the luxury goods for the drawing rooms of the elite and the common areas of those aspiring to gentility.

Drawing on the burgeoning interest in the consumer or marketplace revolution of the 17th and 18th centuries, the participation of the African diaspora as consumers reveals itself when you think about the dandy. Since Africans participated in transatlantic trade and, while in the New World, were clothed and fed, had visual—if not material—access to the latest goods and fashions, and frequently produced the foods, clothing, dyes, wigs, etcetera consumed by Europeans, the juxtaposition of their bondage and their adornment complicates the idea that Black people merely copied modern style. That, as many assumed during the rise of minstrel shows and the cakewalk, that they took their cues from white Americans and Europeans.

The dandy asks us to rethink and reconfigure beliefs about how Black people’s self-fashioning being in reaction to modernity instead of being the primary driver of it.

Walter A. Dyer, "Wedgwood Plaques and Medallions," The New Country Life (March 1918)

Hicks, “Introduction,” The Oxford Handbook of Material Culture Studies, 26.

Gerritson and Riello, 113

Appaduri, 33

Mintz, 43

Beckert, xv

Anishanslin, 17

Bushman, 62

Anderson, 8

Without Black bodies, there is no modern world—no refinement, no gentility, no empire. Angela Tate’s essay tears through the velvet drapes of “civilization” to reveal the Black hands that built it, dressed it, adorned it, and were consumed by it. From the dandy’s subversive swagger to the mahogany sideboard crafted in chains, Africans Maketh the (Wo)Man insists on Black materiality not as embellishment, but as foundation.

Tate’s excavation of Wedgwood’s abolition medallion and the Met Gala’s dandy revival draws a throughline from 18th-century commodification to 21st-century costume, refusing to let style be divorced from structure. Black fashion, she argues, isn’t mimicry—it’s a generative force, shaping the aesthetic and philosophical parameters of modernity itself.

For those of us reclaiming African mythology, this is connective tissue. The spiritual, symbolic, and sartorial have never been separate. They are technologies of memory, power, and survival. The dandy, like the deity, wears what the empire cannot contain.

Stunning article.