What do we do about a problem like Meghan?

On Bridgerton, Meghan Markle, and history. Brief rumination on the Netflix period drama and ownership over the past.

This was originally written in 2021, but revised in response to Meghan’s own Netflix productions.

It’s not a coincidence why the Duke and Duchess of Sussex have championed internet safety as one of the core pillars of their foundation. Since being exposed as Prince Harry’s girlfriend way back in late summer of 2016, Meghan (née Markle) has been the target and the subject of intense scrutiny—and racism and sexism. Dr. Moya Bailey developed the concept of misogynoir to explain the specific violences that Black women face, particularly in digital spaces. Bailey’s most recent work, Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance, delves into the ways Black women have developed internet communities and methods to push back against the abuses and harassment.

The Glitch Charity, based in the UK, released a report in 2023 about digital misogynoir to demonstrate the harms against Black women online. They explicitly state:

Digital misogynoir is the continued, unchecked, and often violent dehumanisation of Black women on social media, as well as through other forms such as algorithmic discrimination. Digital misogynoir is particularly dangerous because of its ability to incite offline violence. For example, after spending time on far-right social platforms, white supremacist Dylann Roof went on to murder nine Black church members, seven of whom were women, while they were at bible study. In the UK, misogynoir has recently been prominent in the sustained and targeted harassment of Meghan Markle in the tabloid press and online.

Since 2016, the print and online media industries have built an empire on manipulating public perception of Meghan, Duchess of Sussex. The fever pitch of digital abuse reached its peak in 2019 when Meghan was pregnant with her first child and again in 2020 when the Duke and Duchess of Sussex stepped back from their position in the British royal family to live independently in the United States. Since then, the digital harm has been steady, with spikes of intensity whenever the couple releases projects or emerges on the public stage together or separately (though Meghan’s appearances—and absences—are more substantially targeted than Harry’s).

The release of Harry & Meghan on Netflix in late 2022 gave the couple space to tell the story on their own terms, and also attempted to place their relationship—and specifically the racist and negative reactions to Meghan—in historical context. Black British thinkers Afua Hirsch [author of Brit(ish): On Race, Identity and Belonging] and David Olusoga (author of Black and British: A Forgotten History) drew links between the formation of race and anti-Blackness and the British empire, a history that continues to be contested and criticized by attempts to force Britain to reckon with its racial past. Dr. Corinne Fowler in particular has drawn controversy for the National Trust’s Colonial Countryside Project, which argues that “British country houses were influential centres of colonial wealth and bureaucracy.” All of which revises ideas about what is Britishness and what is the role of Black people in British history.

Meghan’s individual voice (on her podcast, Archetypes) drew the same abuses and spiked more digital misogynoir, and it has reemerged with the release of the trailer for her upcoming Netflix series, With Love, Meghan. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns, millions of people turned to online spaces to make community and engage with others at a time when physical interactions were dangerous. Black and brown internet users participated in and developed cycles of online microtrends, with “cottagecore” being a particular microtrend and micro-community that young women in particular gravitated towards.

(Image credit: @styleidealist via WhoWhatWear)

Images of Black and brown women wearing prairie dresses, carrying flowers, making bread, enjoying picnics and tea parties, and otherwise indulging in pastoral frolics drew controversy. In her 2020 article in Lithium Magazine, Irma K pushed back on the critiques about romanticizing the past and pushing tradwife imagery, arguing that they

aren’t just glamorizing an aesthetic; they’re politicizing a lifestyle. The movement embodies an aesthetic, sure, but it promotes real, actionable choices. With its focus on sustainability and self-sufficiency, cottagecore shows that everyday actions have profound political significance.

This argument finds an echo in the other movement that emerged in 2020, where longtime vintage aficionado and band leader Dandy Wellington coined the phrase “Vintage Style NOT Vintage Values” in response to the experiences people of color and LGBTQ+ vintage lovers.

In Shondaland’s first production for Netflix, Bridgerton, the hero Simon, Duke of Hastings strides arrogantly into the frame, arches an eyebrow in response to witty repartee, and his muscled, well-dressed physique sends ballrooms of fluttering debutantes into a swoon.

To audiences accustomed to a steady diet of period dramas—often Jane Austen adaptations shipped across the pond to Masterpiece Theater—and historical romance novels, this is a familiar figure. A figure frequently duplicated across dozens of romantic historical entertainment inspired by the likes of Darcy, Heathcliff, Maxim de Winter, Rochester, and more. Simon’s cravats are starched and tied high, his carriage erect, his arrogance intriguing, and his glances are suitably smoldering—so why is this figure immediately rendered alien when these familiar visual tropes are performed by a Black man?

History has long been a battleground over the power vested in who controls access to narratives about the past; however, when history is materialized in popular culture, this battle is obscured under the demands for “accuracy.” Furthermore, historical popular culture has developed visual codes across decades over who does and does not belong in the rarefied worlds of royalty, aristocracy, and the other sumptuous settings favored by period drama and historical fiction aficionados. And as seen by the continued racism and harassment faced by Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, this visual code has real world implications wherein what consumers envision of the past—and of fantasies about powerful, influential, elite spaces—through consumption of history-based entertainment transfers to opinions and assumptions about who should occupy the past (and these spaces) in everyday life.

Early reviews of the drama approached the series with the assumption that it was another Downton Abbey, or an “updated” period piece. Some early reviews did view it as a romance genre adapted and trotted out the stereotypes about “bodice rippers” that the genre has struggled to shake off forty years after its emergence as blockbuster fiction. The most vocal responses to Bridgerton have come from academic historians, a profession who has always had a contentious relationship with period dramas and other history-based entertainment.

Furthermore, the choice to make the fictionalized fantasy Regency setting include people of color (POC), a decision known in fandom circles as racebending, caused many scholars—particularly scholars of Haitian history—to decry the downplaying of slavery and colonialism, to discuss what changing the characters’ race means for the plot, and the erasure of Haiti and its own aristocracy in the early 1800s. Romance readers and writers also had their own conversations, many of which dealt with the issues of consent and translating Regency romance speak for audiences, not to mention the decades’-old debates about “accuracy” and POC in historical romance—and the sting of both Quinn’s rejection of POC in her novels on a panel at the 2018 Romance Writers of America conference and the backlash from Quinn’s readers when she revealed the casting of Regé-Jean Page as Simon.

As a history blogger, a museum curator, a longtime reader and writer of historical romance, a period drama aficionado, and as someone soon to wrap up a PhD in History, I stand at the intersection of these debates. In particular, I remember the massive popularity of ITV’s Downton Abbey (2010-2015) and the uneasy response to the addition of Jack Ross (Gary Carr) in season four. Ross was an African American jazz musician who briefly romances the rebellious Lady Rose Macclare (Lily James), and his presence created a flurry of responses about “accuracy” and the interracial romance aspect. It doesn’t help that as the series wrapped up, an esteemed British actor opined that the show was popular in the US because it lacked Black characters. Coincidentally(?), Jack Ross also happened to debut on Downton Abbey at the same time the BBC premiered its 1930s jazz-based period drama, Dancing on the Edge, starring Chiwetel Ejiofor as bandleader Louis Lester (Mr. Selfridge also made an attempt to be inclusive in its final season, set in the 1920s, with the introduction of Tilly Brockless).

(BBC’s Dancing on the Edge, 2013)

I used Edwardian Promenade as a vehicle to introduce viewers to the presence of Black people in interwar Britain and the influence of jazz ; however, the still-entrenched beliefs that period dramas—that the past itself—is the sole playground for white characters is entangled with the uses people make of the past, their anxieties about the present, and, to be frank, the way history is often weaponized in ways many don’t recognize except to understand that when they see the past, they attempt to see themselves. And current events have shown that this attempt has real-world implications, ranging from the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol building to the targeted harassment of prominent women of color.

In 2015, when a friend asked if I wanted to take part in an anthology about Armistice Day, I immediately said yes! At the time, I was struggling with my writing career—primarily because I had started to become uncomfortable with the notion that I would have to only write about white aristocratic characters in order to be published. I had already self-published a two-part historical saga about a British family on the brink of WWI, and as much as I loved the characters there was still a part of me that felt I’d given into the pressures of the genre. I am happy with my contribution to Fall of Poppies, After You’ve Gone, but it was written in an incredibly self-conscious vacuum.

In that it was a moment to reflect on why historical fiction is so white, what do popular tropes and conventions mean for readers and writers, and what does it mean to insert POC into this? And as the sole woman of color contributor writing about characters who shared my background, the self-consciousness also included Representation—that old chestnut about having to be “the best” in order to prime readers to expect other authors of color to provide the same experience as a white author; mediocrity only supports the preexisting beliefs about “quality.” But overall, I also hoped that my inclusion was a strong argument that we were there too.

Ironically, this very argument is what causes so much uneasiness and disruption in Bridgerton. In episode four, a tête-à-tête between Simon (Page) and Lady Danbury (Adjoa Andoh) attempts to explain why Black and Asian characters exist in this Regency world by drawing on the longtime belief that Queen Charlotte of England was of African descent. Tracing this African descent uncovers the underwritten stories about the African presence in Europe before the 20th century, but it also asks if Africans did exist in the Regency period, did the transatlantic slave trade also exist?

The handwaving over POC characters sits uneasily with the actual history of the early 1800s, while also contending with historical romance’s uncomfortable relationship with including POC—and the complete fantasy world that has been dubbed “Alamackistan” (which is why many ask why POC cannot be characters?).

Coincidentally, the first Lifetime fictionalized drama about Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s relationship draws on this as well, with the movie ending with a scene of Queen Elizabeth II showing Meghan (Parisa Fitz-Henley) and Harry (Murray Fraser) a painting of Queen Charlotte in her palace. Bridgerton’s Queen Charlotte (Golda Rosheuvel) swans about palaces and ballrooms in a variety of hairstyles that reflect Black textures, from braids to locs to afros, further cementing the visual aspect of her supposed African heritage. These visual cues are even more fascinating when taken with the various responses to the neat locs (and nose stud) of Meghan’s mother, Doria Ragland.

We were apparently there too—we are there—but how? And why?

In April 2020, British writer Liv Siddall tweeted her dramatic exit from Instagram in response to seeing a photo of the then-unknown Paula Sutton, picnicking and reading a book on the verdant grass of her country estate in a wide-brimmed hat and green dress. Though Sutton’s face is covered by the hat, her limbs are clearly brown, marking her—through the eyes of Siddall and many others who chimed in—as undeserving, illogical, jarring in such a context. Sutton, a former fashion editor, used her Instagram to display her joys in her country life, her vintage decor, and her homemaking. In the context of the aforementioned survey on British country houses and slavery, the concept of a Black woman enjoying the lifestyle and housing that was and is marked as for whiteness, for power, and was constructed to conceal the slavery-generated wealth was inconceivable.

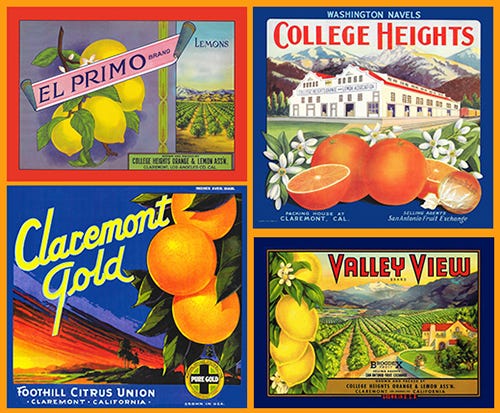

Perhaps the linkage can be viewed as less tenable in the case of the criticism of Meghan’s upcoming lifestyle show, which draws on similar visual rhetorics of romanticism and domestic life. California appears to be dissimilar to the British countryside—or was it? If you’re from the Golden State, you are aware of the many Spanish missions that dot the state from north to south, which are/were colonial sites of brutal oppression of indigenous peoples. Furthermore, much of the ideas around and about California were created by boosters in the early 20th century to encourage white settlement of the West to counteract the presence of Black and brown people. Dr. Paul J. P. Sandul describes this particular phenomenon in his book California Dreaming: Boosterism, Memory, and Rural Suburbs in the Golden State. Back in 2016, I was part of the team to reinterpret and reimagine how the California Citrus State Historical Park told the story of the citrus industry’s influence on California’s social, cultural, and economic growth, and the stories the state tells itself about who was involved in this history.

(Claremont Citrus Fruit Crate Labels - Claremont Heritage)

The image of Meghan participating in this storytelling has sparked controversy and claims about her pushing “tradwife” content. But is it criticism of the participation itself, or is it once again about a woman of color, a Black woman, utilizing the ideas and strategies that continue to be considered the purview of whiteness only and thus disrupting the belief that people of color—women in particular—are mere commodities that allow their oppressors to develop and enjoy prosperity?

The vitriol that Megan receives is abhorrent. I cannot even fathom how this poor girl gets through a day when every single thing she does is framed as conniving, vindictive, toxic. She genuinely seems like such a lovely human being.

What a thorough article. Not everybody is ready to see us in certain spaces.